Cybercrime campaigns can last days or months, but the malicious actors behind them can be active for years.

As it’s often difficult to have first-hand information about the evolution of specific gangs (e.g., changes in membership and leadership, or motivations behind actions), the threat intelligence community generally resorts to tracking the most observable aspects of these criminal enterprises: the malware that is delivered to the victims and the infrastructure that is used to control compromised systems and collect sensitive information.

Malware campaigns are almost always trans-national in terms of both targets and infrastructure, covering multiple countries and sometimes spanning multiple continents. Therefore, it’s difficult to carry out coordinated law enforcement efforts (especially given that many law enforcement agencies are already stretched thin), and the defenses against these threats are primarily localized to specific countries or organizations.

However, sometimes the cyber threats are so egregious that they trigger the attention of a large group of people, resulting in major takedown operations such as 2011’s “Operation Ghost Click” or the Microsoft-led takedown of the TrickBot infrastructure in October 2020.

It was one of these efforts, and a historical one in this case, that brought down Emotet at the end of January 2021 — a feat that many considered impossible.

“Operation Ladybird” saw the law enforcement agencies of multiple countries (including the US, the UK, Canada, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Ukraine, and Lithuania) cooperate to eradicate the Emotet infrastructure (see Figure 1).

Emotet, introduced in 2014 as a banking Trojan, has been at the forefront of the malware landscape. Through the years, this threat grew to become the most effective way to deliver a number of malicious payloads, from credential stealers to ransomware, and caused financial losses that some assessed to be over two billion dollars.

At the moment of the takedown, Emotet controlled more than a million compromised computers.

Global Impact

After hearing the news about the Emotet takedown, we started looking at the network detection event generated by our Advanced Threat Protection sensors.

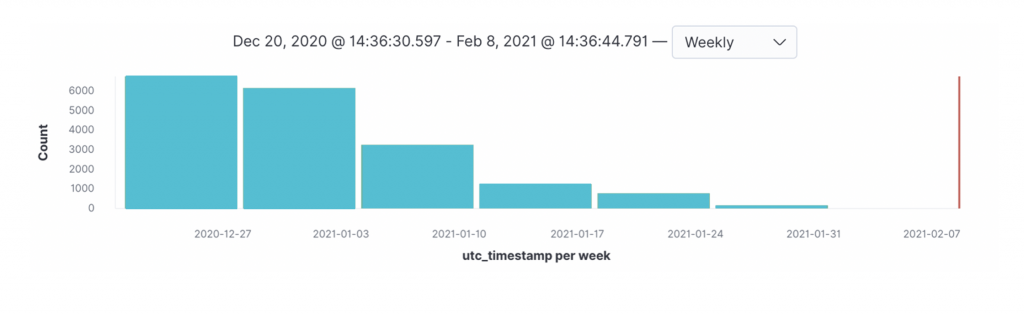

Looking at this telemetry (see Figure 2), we could clearly see a dramatic decline of Emotet command-and-control events (although a drop in activity has been observable since the first week of January).

Unfortunately, the takedown of the Emotet infrastructure does not permanently disrupt all cybercrime operations. Cybercriminals follow opportunistic strategies and once a pay-per-install infrastructure is removed, they will quickly leverage a new intermediary to deliver their payloads. It will be very interesting to observe, in the next few weeks, which cybercriminal operation will “pick up” the customers of the now-disrupted Emotet delivery service.

Impact on Financial Sector

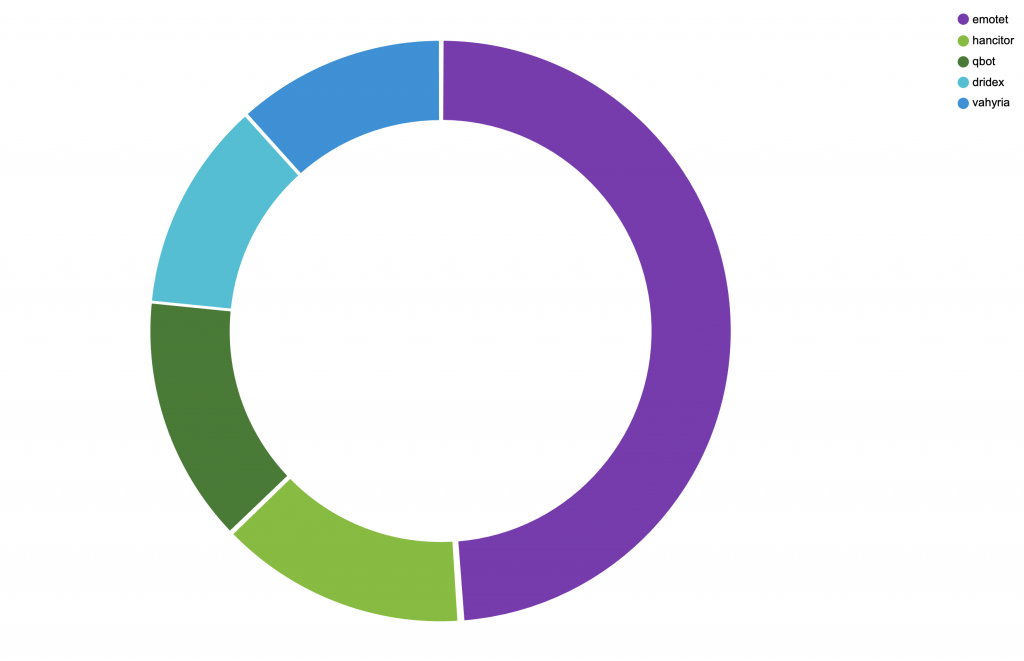

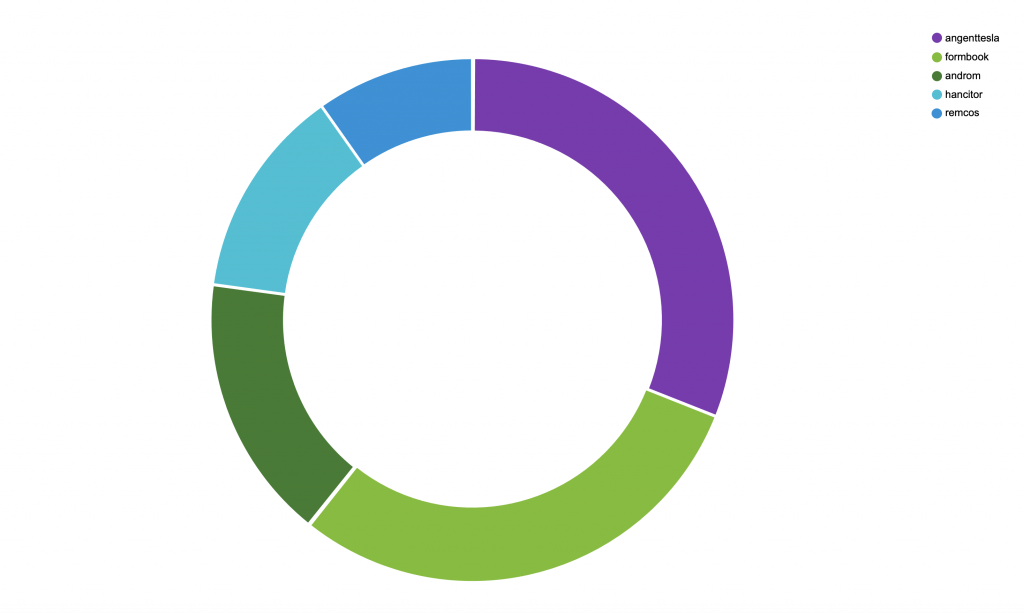

We looked through our telemetry with a specific focus on the financial sector (a vertical often battered by the worst the threat landscape has to offer), and we found a clear change of malicious attachments and HTTP downloads between the last two weeks of January (see Figure 3) and the first two weeks of February (see Figure 4).

Note that these threats are quite specific to our telemetry and are limited to the time span around the Emotet takedown operation. (For a description of the most prevalent threats in the financial sector in the past six months, see Sidebar 1).

Before “Operation Ladybird”, Emotet was certainly a major player in terms of observed downloads and attachments, followed by Hancitor, Qbot, Dridex, and Valyria. With one caveat: It’s often difficult to really understand the role of these threats, as they frequently represent a vector for one another. For example, Valyria is a downloader that typically leverages weaponized Office documents to download other components, among which Emotet itself. In other scenarios, Emotet was a conduit for Qbot. As a result, these threats often overlap and have different behaviors depending on the deployment context.

Sidebar 1: The five most prevalent threats in the financial sector in the past 6 months

The financial sector is a high-priority target for cybercriminals, who are looking for banking credentials and access to financial applications (such as bitcoin wallets) that can be monetized in a straightforward manner.

As it happens in many other domains, attacks are usually carried out using email as an initial vector for the execution of a trigger (usually the opening of an attachment or the clicking of a link) that activates a number of subsequent steps, which include the downloading of additional malware components, attempts to achieve persistency, and the abuse of benign tools – such as PowerShell scripts or remote execution mechanisms – to spread laterally.

In our past telemetry, we have observed specific threats being particularly active in the network of our customers in the financial sectors, and, at the same time we have been monitoring large-scale campaigns whose analysis has been made public.

These are the top five threat that we have seen appear in these threat intelligence sources.

1. Emotet: Emotet is a Trojan that mainly spreads through spam emails containing either malicious macro-enabled documents or links. Emotet allows criminals to monetize attacks via information stealing, email harvesting, and ransomware distribution. Since its inception in 2014, this threat underwent a number of evolutionary steps, until its network infrastructure was taken down at the beginning of 2021.

2. Dridex: Dridex is a banking Trojan, which acts as banking credential stealer, a ransomware delivering system, and a remote access control tool. This threat is often delivered through macro-enabled MS Office documents attached to emails.

3. Trickbot: Trickbot is a threat that targets the financial sector, providing modules that support the theft of banking credentials and cryptocurrency, as well as ransomware. This threat was the target of a takedown initiative in October 2020; even though the threat infrastructure took a hit, the cybercriminal gang behind it recovered and restarted its activities.

4. Qbot: Qbot, also sometimes known as Qakbot, is a versatile threat that supports a number of modules (from remote access to credential theft). A notable technique recently used by this threat was to observe email threads and inject themselves in existing threads, increasing the chances that a user would deem the corresponding attachment as a legitimate one.

5. Hancitor: This less-known threat has experienced a comeback at the beginning of 2021. This threat acts mostly as a delivery mechanism for a plethora of other threats, and it has often used DocuSign documents to entice the victim into activating the email’s malicious attachments.

After the takedown, the threat landscape observed by our sensors changed considerably. Predictably, Emotet infections decreased substantially while new threats (such as Agent Tesla and Formbook, two popular RATs/keyloggers) became more prevalent.

Conclusions

The results shown above clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of takedown efforts.

Entire threats disappear from the landscape, severely disrupting the activities of cybercrime gangs and making the Internet a safer place, or at least one populated by less sophisticated (and easier-to-detect) threats.

However, the effect is only partial, and temporary. Even if the threat landscape has suddenly shifted, in the coming weeks we will see how cybercriminals respond to these actions. One can only hope that restoring their operations will cost them time and money, and, possibly, lead to mistakes that will eventually result in actual convictions.