Data availability is a core competency of enterprise storage systems. For decades, these systems have attempted to deliver high levels of data availability while ensuring that performance and space efficiency expectations are also met. Achieving all three at the same time is not easy.

Erasure coding has played an important role in storing data in a resilient yet space-efficient way. This post will help you better understand how erasure coding is implemented in VMware vSAN, how it is different from what may be found in traditional storage arrays, and how best to interpret an erasure code’s capabilities with data availability.

The Purpose of Erasure Coding

The primary responsibility of any storage system is to give back the bit of data that has been requested. To ensure it can do this reliably, storage systems must store that data in a resilient way. A simple form of data resilience would be through the use of multiple copies, or “mirrors” that would help maintain availability in the event of some type of discrete failure in the storage system, such as a disk in a storage array, or a host in a distributed storage system like vSAN. One of the challenges with this approach is storing full copies of data becomes very costly in terms of capacity consumption. An additional copy would double the amount of data stored, while two additional copies would triple the amount of data stored.

Erasure codes are used to store data in a resilient way, but with much more space efficiency relative to traditional mirroring of data. It does not use the approach of copies. It spreads a unit of data across multiple locations—where each location may be considered a point of failure, such as a disk, or in a distributed system like vSAN, a host. The chunks of data create a “stripe” along with additional parity data created when the data is initially written. The parity data is derived from mathematical calculations. If any of the chunks are missing, the system can read the data from the available portion of the stripe and perform a calculation with the parity to fill in the hole of the data missing. It can then fulfill the original read request in-line, or reconstruct the missing data to a new location. The type of erasure code will determine if it can tolerate the absence of a single chunk, two chunks, or more while maintaining data availability.

These erasure codes offer substantial capacity savings compared to traditional mirrored copies of data. The space savings are determined by the characteristics of the erasure code, such as how many failures the erasure code is designed to tolerate, and how many locations it is distributed across.

Erasure codes come in all shapes and sizes. They are typically identified by the number of data chunks and the number of parity chunks. For example, the notation of 6+3 or 6,3 means that the stripe is composed of 6(k) data chunks and 3(m) parity chunks, totaling 9(n) chunks in the stripe with parity. This type of erasure code could tolerate up to any three chunks failing and the data remaining available. It can achieve this resilience with an additional 50% of capacity used.

But all is not perfect with this approach to storing data resiliently. I/O operations can become more complex, where a single write operation may translate to several read and write operations, known as “I/O amplification.” This can slow down storage processing along with demanding more CPU resources and more bandwidth across any type of resource bus. If done right, erasure codes can be used to combine resilience with performance. For example, the innovative architecture in ESA defies common performance penalties of erasure codes, where a RAID-6 erasure code in ESA can deliver the same or better performance than a RAID-1 mirror.

Data Storage in vSAN versus a Storage Array

Before we compare erasure codes in vSAN to traditional storage, let’s do a quick comparison of how vSAN stores data compared to a traditional storage array.

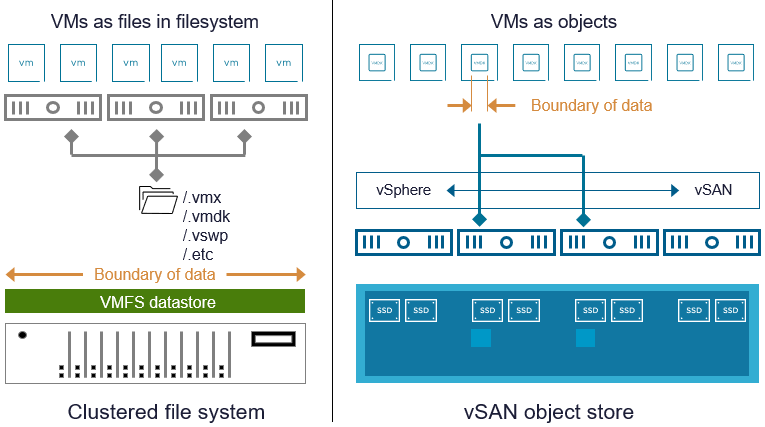

Storage arrays commonly present a large pool of storage resources in the form of a LUN. In the context of vSphere, it is formatted as a datastore with VMware Virtual Machine File System (VMFS), where multiple VMs will reside. SCSI commands are passed from the VMs through the vSphere hosts and onto the storage system. This formatted datastore on the storage array spans across a large number of storage devices in its enclosure, meaning that there is not only a large logical boundary (a clustered filesystem holding several VMs), but a large physical boundary (spanning multiple disks). Like many other conventional file systems, this clustered filesystem must remain pristine with all metadata and data readily available.

vSAN takes a much different approach. Rather than use a classic filesystem with a large logical boundary of data spread across all hosts, it uses a small logical boundary of data for its entities. Examples would include a VMDK of a virtual machine, a persistent volume for use by a container, or a file share provided by vSAN file services. This is what makes vSAN analogous to an object store, even though it is block storage using SCSI semantics, or file semantics in the case of file shares. For more information on objects and components in vSAN, see the post: “vSAN Objects and Components Revisited.”

Figure 1. The use of a clustered file system on a storage array, versus an object store in vSAN.

This type of approach sets up vSAN for all types of technical advantages over a monolithic clustered filesystem on a storage array. Erasure codes are applied to objects in an independent and granular way. It allows customers to design vSAN clusters however they wish, whether it be a standard single site cluster, a cluster using fault domains for rack-awareness, or stretched clusters. It also allows for vSAN to scale in ways that cannot be matched with traditional approaches.

Comparing Erasure Codes in vSAN versus Traditional Storage

With a basic understanding of how both traditional arrays and vSAN provide storage resources, let’s look at how they approach erasure coding differently. These comparisons assume simultaneous failures, as many storage systems have methods of dealing with single failures over a period of time.

Storage Array

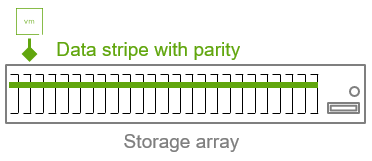

In this example, a traditional storage array uses a 22+3 erasure code (k=22, m=3, n=25).

Figure 2. A storage array using a 22+3 erasure code for a LUN or datastore.

Advantages:

- Relatively low capacity overhead. The additional capacity consumed by parity data needed to maintain availability in the event of fault domain (storage device) failures is about 14%. It is achieving this low overhead by spreading the data across a very large quantity of storage devices.

- Relatively high level of failures it can tolerate (3). Any three storage devices can fail and the volume will maintain availability. But as noted below, this is only part of the story.

Trade-Offs:

- Relatively large blast radius. If the number of failures the array is designed for is exceeded, its boundary of impact is quite large. The entire array may potentially be impacted in such conditions.

- Only protects against storage device failures. Erasure codes in storage arrays only protect against the failure(s) of storage devices. Arrays can be subject to significant degradation in performance and availability if other types of failures occur, such as failed interconnects, failed storage controllers, bad firmware updates, etc. No erasure code can maintain data availability if you lose more storage controllers than the array can tolerate.

- Relatively high performance impact during or after failure. Failures using large k & m values can demand a lot of resources for repairs, and be more prone to high tail latency.

- Relatively high potential points of failure per parity. The ratio of 8.33:1 reflects a high number of potential points of failure versus the parity bit(s) that contribute to maintaining availability. A high ratio highlights higher fragility.

The last bullet point is extremely important. Erasure codes should not be judged solely on their stated level of resilience (m), but rather, by the stated resilience versus the number of potential points of failure it is protecting against (n). It provides a better approach to understanding probabilistic reliability of a storage solution.

vSAN

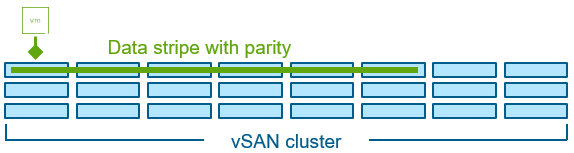

In this example, we’ll assume a 24 host vSAN cluster where a VM’s object data is prescribed a RAID-6 erasure code of 4+2 (k=4, m=2, n=6). Note that the components that make up a vSAN object using a RAID-6 erasure code will have both data bits and parity bits. As Christos Karamanolis describes in the post “The Use of Erasure Coding in vSAN” (vSAN OSA, circa 2018), vSAN does not create dedicated parity components.

Figure 3. vSAN using a RAID-6, 4+2 erasure code for a vSAN object.

Advantages:

- Relatively small blast radius. A cluster that exceeds two simultaneous host failures will only affect some objects, but does not take down the entire datastore.

- Protects against a variety of failure conditions. Erasure codes in vSAN can account for failures in discrete storage devices, hosts, and explicitly defined fault domains such as rack.

- Relatively low performance impact during or after failure. The smaller k values help reduce computational effort in repairs.

- Relatively low potential points of failure per parity. The ratio of 3:1 reflects a low number of potential points of failure versus the parity bit(s) that contribute to maintaining availability.

Trade-Offs:

- Lower absolute tolerance of failures within an object (2). The stated resilience of vSAN’s 4+2 erasure code is less. But note that the boundary of failure (the object) is smaller, and it has a much lower potential points of failure per parity.

- Relatively higher overhead. The additional capacity consumed by parity data needed to maintain availability in the event of a fault domain (host) is 50%.

Even though vSAN RAID-6 erasure code protects against 2 failures as opposed to 3, it is extremely robust due to the relatively few number of potential points of failure: just 6 versus 25. This gives vSAN’s 4+2 erasure code the technical advantage over a storage array’s 22+3 erasure code when comparing reliability as a result of failure probabilities.

With vSAN using an erasure code with a small “n” value, this provides much more flexibility for our customers to build clusters for all types of scenarios. For example, our RAID-6 (4+2) erasure code can run on as few as 6 hosts. A 22+3 erasure code would need, in theory, at least 25 hosts within a cluster.

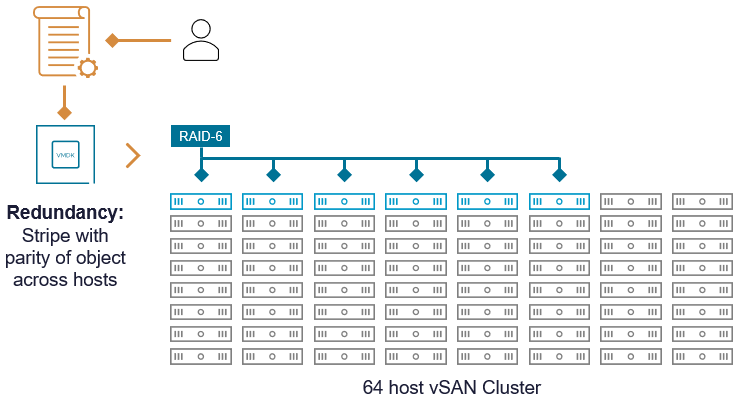

Decoupling Cluster Size and Availability

vSAN RAID-6 erasure coding remains a 4+2 scheme regardless of the cluster size. When a storage policy of FTT=2 using RAID-6 is applied to an object, it means that it can tolerate two simultaneous host failures of the hosts where the object resides. It applies to the state of the object, not the cluster. Other failures on other hosts have no relevance to the state of this object, other than helping to regain the prescribed level of resilience of an object upon any type of failure. vSAN will recognize these other hosts as potential hosts it can use to reconstruct the missing portion of the stripe with parity.

Figure 4. Object placement with relation to cluster size.

This approach allows vSAN to decouple the relationship between cluster size and availability. While many scale-out storage systems become more fragile as they scale out, vSAN’s approach reduces the risk as the cluster scales. For further information on vSAN availability and failure handling, see the “vSAN Availability Technologies” document on the VMware Resource Center.

Summary

Erasure coding is a powerful technique to store data in a highly resilient, yet space-efficient way. But not all erasure codes are created equally. vSAN uses erasure codes that provide an optimal blend of durability, flexibility, and space efficiency across a distributed environment. Paired with opportunistic space efficiency features like vSAN’s data compression, and ESA’s new global deduplication capabilities in VCF 9.0, your vSAN storage is more capable than ever.

Discover more from VMware Cloud Foundation (VCF) Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.